If you’ve ever worked in a kitchen (and I mean a real kitchen where you and others aren’t just slapping things on a conveyor belt and chucking a handful of pre-shredded, frozen lettuce on a bun before wrapping it as quickly and poorly as possible), you know how chaotic it can be. It’s hot and cramped, there’s a lot of yelling in multiple languages, and everyone is sweating like they’re in trouble. There are egos, feuds, petty competitions, and everything else that an HR department strives to squash. Feelings matter less than ability; the language is coarser than the salt and, on a good day, the laughter flows as easily as the snapped commands.

These are all traits that “The Bear,” which is available to stream on Hulu, not only captures but manages to humanize as it chronicles the lives of Carmen “Carmy” Berzatto (Jeremy Allen White), a prestigious chef brought home to run his late brother’s restaurant, and the rest of the rag-tag gang of culinary misfits (read: caricatures of the restaurant industry) that serve as the staff of The Beef. With so many restaurant-industry tropes on the menu, let’s give you some tasting notes.

**Spoilers ahead!**

The Tortured Genius Chef

Carmy is an award-winning chef, yet spends most of the first season fighting with the crew of The Beef to do things his way. We see flashbacks to the intense abuse he suffered at the hands of his superiors (played by Joel McHale, who does an excellent job of being a royal asshole) in his Michelin-rated restaurant career — a restaurant-industry stereotype — and we see him actively trying to break that cycle with his new (to him) staff.

We also see him pouring all his energy into keeping the restaurant afloat, ignoring his own need to grieve his brother or otherwise process any of the intense emotions he’s experiencing. It’s another common trope in the restaurant business, but one that “The Bear” manages to make palatable. We love a tortured, brilliant protagonist, and like Carmy sets out to do with The Beef’s menu, “The Bear” elevates this conventional, fan-favorite fare by offering nuance and depth.

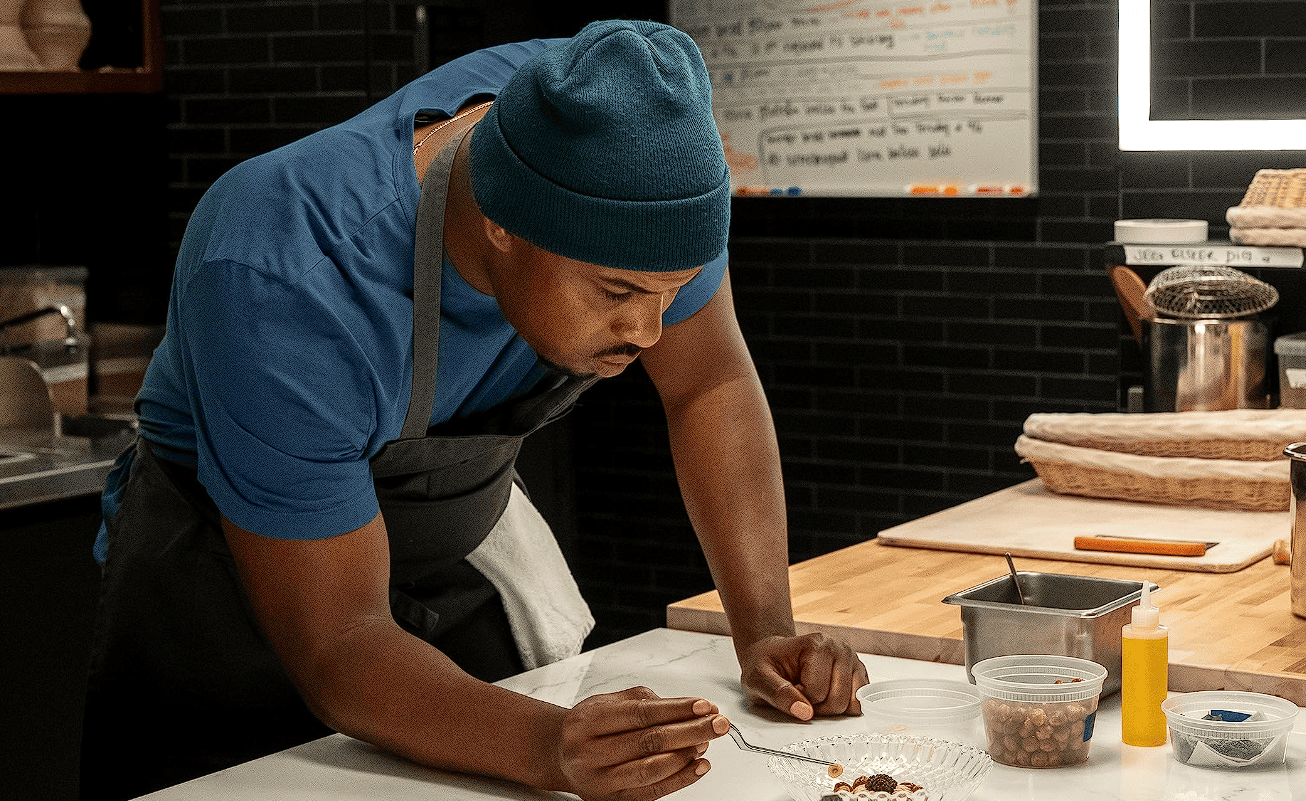

The Ambitious Sous Chef

Carmy’s right hand, Sydney (Ayo Edebiri), is an ambitious young chef (or is it “Jeff?”) who, after a failed catering venture, is looking to make a name for herself in the restaurant world. She joins the staff at The Beef because of Carmy’s prestige, and her ambition is matched by her inexperience — yet another old standby on the restaurant trope menu, left overnight to rise into a three-dimensional being by introducing her family dynamic in the second season.

The Classic Toxic Line Cook (or Dishwasher, Cashier, etc.)

Oftentimes kitchens and restaurants serve as a magnet for people you could generously describe as “coarse,” like Richie (Ebon Moss-Bachrach), a divorced father and walking HR violation who took over The Beef before Carmy arrived. If there was ever a negative stereotype about line cooks and restaurant managers, it’s present in Richie, right down to his casual misogyny (he calls Sydney “sweetheart” upon meeting her), drug use (he sells cocaine out of the alley behind The Beef to keep things afloat during a rough patch), and stubborn attitude (he actively combats any changes to The Beef).

After his character is left to simmer throughout the first and second seasons, we see Richie as a man who believes all his best days are behind him and tries to hold on to some semblance of home and familiarity in a world that he seems to feel has moved on without him.

The Career Cooks and Old-Timers

We can’t forget Tina (Liza Colón-Zayas) and Ebraheim (Edwin Lee Gibson), the two older immigrant cooks who, as The Beef transitions into The Bear, end up attending culinary school, or Marcus (Lionel Boyce), the resident baker and pastry chef who gets so wrapped up in his doughnut experiments that he gets behind on the cakes for dinner service. Tina and Sydney start “The Bear” by exemplifying a classic restaurant industry beef: the new sous-chef butting heads with the veteran staff who are used to doing things a certain way.

Ebraheim finds himself having “fish out of water” moments when surrounded by young chefs during class, and Tina and Sydney eventually develop enough mutual respect that Sydney asks Tina to be the new sous-chef, taking these characters and tropes out of cookie-cutter TV land and allowing them to develop a little nuance.

The Hole-in-the-Wall Restaurant

The Beef becomes something of a trope: The dilapidated, rundown facility, riddled with mold, health code violations, and dead raccoons in the ceiling quickly establishes itself as a money pit, lending credence to the age-old riddle: How do you turn a billionaire into a millionaire? Answer: Open a restaurant.

What struck me the most about “The Bear” wasn’t the perceived accuracy in which it portrayed a struggling, mom and pop restaurant; it was what held the staff together as they held the restaurant together, which is a cliche in and of itself: love.

None of our core characters live a picture-perfect life. Just ask your local dishwasher about his alimony payments, and you’ll see how accurate this portrayal of the restaurant industry seems to be. Each of our characters has some form of grief that they have to work through, whether it be for their brother, mother, failed marriage, or childhood. If grief is just “love with no place to go” (I can’t remember if it was a therapist or a Hallmark card that told me that, but I promise I have a point), then in “The Bear,” Carmy and the rest of his friends and staff have found an outlet for that love: the food and their restaurant. You get this sense that if they couldn’t lose themselves in their work, they would ultimately lose themselves completely.